Let's Talk About Periods

Menstruation. Time of the month. Aunt Flo. Call it what you want as long as we finally start talking about the reality for menstruating athletes.

We are in the home stretch of Women’s History Month, a holiday of sorts celebrated for obvious reasons. To honor the females who cracked the glass and those who shattered it. To honor the women who have fought and keep fighting for equal pay and other measures of equality. We honor the endless contributions of badass women to American society particularly those who did it without the inherent respect bestowed upon their male peers. And for most of history, they did it without their male counterparts having a clue that they were navigating the tangled web of hormones that ebb and flow each month. Yeah, I’m taking about our periods.

I still get the heebie jeebies thinking about the short white shorts I had to sometimes wear as a high school track athlete. How my fellow athletes and I had to suffer through our periods while competing, trying to put aside extreme fear of leakage. Not to mention trying to conform to the idealized body type. Unless you were lean and hipless, you were SOL. Things aren’t much better in the the couple of decades since I was a high school athlete.

According to a Tucker Institute report, girls are dropping out of sports at “an alarming rate” between the ages of 11-17, double the amount of boys. This is the range when “girls feel the most pressured to conform to identities shaped by their peers and adults — which includes coaches,” the report states. How utopian bodies are presented on social media isn’t helping matters.

[For a deep dive into this particular aspect of the issue, I highly recommend the ‘Crisis in Girls’ Sports’ episode of Malcolm Gladwell’s Revisionist History podcast.]

So you start with all the unattainable body images, then you add on a menstrual cycle AND you’re probably coached by a man, forget about it. I’m shocked the attrition rate isn’t higher.

We can’t do much about the vacuum of social media other than delete it. And sports, in general, were never concocted around the female body. But as girls drop sports like flies we have a real opportunity and quite frankly, obligation, to normalize discussion of periods.

For too long, any talk of menstruation in athletes has been taboo. As if it’s some kind of embarrassing handicap instead of a natural occurrence. For the most part, athletes talk openly about their periods about as much as NFL players fess up to having a fractured rib. It’s just something the athlete is supposed to deal with. Silently.

One refreshing exception is Mikaela Shiffrin, the most accomplished alpine skier in history. After winning yet another World Cup in Italy last January, Shiffrin told an Austrian news outlet that she did so while in “an unfortunate time of my monthly cycle.” So clueless were these Austrians they translated cycle to bicycle. Bravo to Shiffrin to being so authentic and bonus points for nicely mocking the Austrian reporter.

Shiffrin even took to the time to offer a detailed explanation on the side effects of her cycle.

It’s absolutely fantastic that Shiffrin is confident and successful enough to tell her truth. So how do we take the megaphone and get this info trickling down to youth sports, particularly male coaches of menstruating athletes? How do we, can’t believe I’m about to type this, stop the bleeding. We talk about it.

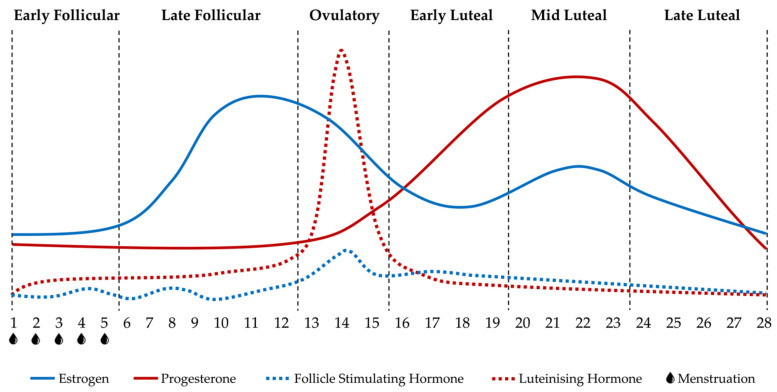

It starts with a basic understanding of the menstrual cycle which occurs monthly and and lasts between 21 and 35 days. There are two main phases, follicular and luteal, But because of the immense fluctuation in hormones such as estrogen and progesterone a menstrual cycle is further broken down into the following sub-phases:

Early follicular, Late follicular, Ovulatory, Early luteal, Mid luteal and Late luteal

The National Institutes of Health published this handy chart adapted from McNulty et al. in their research paper The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2020

Each phase means different things for the athlete. In the early follicular phase when hormones are at their lowest, the body can maximize hard training efforts by digging into stored carbs. Hydration is also easier. During the luteal phase when hormones are sky high, muscle building capacities decrease. That extra dose of progesterone also leads to mood swings, bloating, sleep disruptions and all the other delightful symptoms commonly known as PMS. The research is still fairly new but there’s enough out there to delve deep into each sub phase and how it might impact athletic performance.

As young women are psychology impacted by their changing bodies and perceive their periods as a negative, youth sports organizations have a real opportunity. There’s the opportunity to show empathy to their athletes just by sheer acknowledgement of this pretty monumental aspect of body development. But there’s also the ethical piece of making sure all coaches of menstruating athletes receive puberty eduction. Not only is it the right thing to do, it also serves as a competitive advantage.

A coach may be brilliant as a developer of talent. A coach may hold the highest license possible. But if that same coach is managing a team of players that have mostly started their periods and is clueless about the impact of a menstrual cycle, they’re not doing their job.

Quite frankly, if I were coaching a group of menstruating teens, an ovulation calendar would be my secret weapon. According to the NIH, elite bodies like Chelsea Football Club, along with the U.S. Women’s Soccer and Swimming teams are tracking their athletes’ cycles via ovulation tracking apps. If I know an athlete is in the luteal portion of her cycle and might be a little short on energy, it might temporarily impact positioning. If that same athlete has anemia, I might inquire if they took an iron supplement if that’s part of the routine. If three quarters of my athletes are menstruating, I might alter certain drills in practice. And if cycles are out of whack for any number of reasons, I’d want to know that too and try and understand the culprit. Maybe I’m overtraining them. Maybe they are engaged in a dangerous diet to try and keep Aunt Flo away. Who knows.

There have been some advancements for menstruating athletes like period underwear and an activewear line from Nike called Leak Protection: Period. But if we’re going to rightfully eliminate white shorts for middle and high school athletes and provide a safe safe space where menstruating athletes can feel comfort and not embarrassed, we have to talk about periods. All of us.

So much of the women’s movement is about equality but when it comes to our hormones during child-bearing years we are very much not equal. For young athletes, that should be navigated, understood and celebrated, not taboo.